As part of my ongoing quest to acquire a scrap of legitimacy in this mad desire to listen to and have thoughts about things, I reckon I'd best try and educate my brain with the words of people who actually know about it.

An ungodly hour on Saturday morning therefore found me on a train bound for "that London", and the Goldsmiths Audio Drama Festival 2019, a two day event designed to bring together approximately 100 people in the field (feel free to correct me), and let them have a talk to each other. It's the second year it's been running, and given what I saw at it, it's certainly something that I think should keep going.

At this point I've got about 30 pages of scribbles that I took down over the weekend, so this is likely to be a bit lengthy. To try and maintain some semblance of structure, I'll sneakily just use the programme timings.

Day 1 - SF and Fantasy

10am - Introduction by Tim Crook (Goldsmiths)

Crook opened the event with a pleasingly flippant style, with a nod and a wink to the sponsors (Audible) and a welcome to those present, including students, writers, producers, all of those aspiring to be the above, and many more, such as sneaks like me. He harked back to the early history of radio drama, including the very first two: "X" and "The Greater Power", now unfortunately lost forever to us, but theoretically transmitted eternally through the "aether" to be picked up by distant civilizations (inverse square law not withstanding).

10.15am - Keynote speech by Seán Street (Bournemouth University)

Seán Street expanded on the idea of humanity's need to both tell stories and to be heard, and the ability of radio to reach into a person and become part of their own "inner sound", that hidden monologue we tell ourselves that we can choose to share or keep secret. He tied this to George Eliot's words on the same, about the possibility of us hearing too much, too well, as the development of transmitted speech hinted at a future where we would never be alone with our thoughts. (Draw your own parallels with social media and 24 hour news channels at your leisure. Or indeed the need to silence that booming voice of the internet that is determined to spoil Game of Thrones or Endgame.)

He also visited the stories around Orson Welles' War of the Worlds, namely the ongoing uncertainty as to whether or not, and to what extent, people were taken in by the first fictional radio work intended to seem like it was real. While he didn't come to a firm conclusion, there are a few interesting snippets, for example the fact that a fake news segment in the show was timed to precisely match the commercial break on the other available channel, presumably to catch those switching over to avoid the adverts. It also happened the year after the Hindenburg disaster, and elements of the famous Herb Morrison transmission undoubtedly were used to improve verisimilitude.

There was a final sidestep into the idea of radio having an important place as the still small voice of calm "in a world gone mad!" (to quote about fourteen people). This linked to the idea of War of the Worlds being placed as an analogy for the encroaching creep through Europe of fascism at the time, and a poignant suggestion that that might be something we need today.

11.45am - Writer Panel: SF and Fantasy Audio Drama

Philip Palmer (Goldsmiths) chaired a panel with Judith Adams (Earthsea (Amazon)), Julian Simpson (The Case of Charles Dexter Ward), Sarah Woods (Borderland) and Marty Ross (Arabian Nights).

Adams discussed how she had been a fan of both Le Guin's works and her later critiques of her own work, and how wonderful it was to then work directly with Le Guin to dramatise her earlier works, and revisit some of the authorial choices Le Guin had later reconsidered. This was compared to the "fun" of working with estates, where the author, by nature, has rather less of a say.

Simpson described the difficulty of convincing Radio 4 to do a "fake" podcast, in the style of, funnily enough, War of the Worlds, or many of the faux-investigative podcasts that exist, only finally succeeding when Sounds became a bit of a goer. He found himself a bit surprised by the fact that rather than writing with a writer's room, it was all a bit dependent on him doggedly putting pen to paper, and got slightly in trouble for fake adverts, but managed in the end. (The BBC of course, famously does not allow advertisements on its broadcasts. Other national broadcasters are available.)

Woods talked about how Borderland was developed very heavily from research she had done on the travels of refugees around the world, assembling the overall atmosphere and plot from a number of small anecdotes, to get the story as close to real life as possible. This also raised the point of the value of science fiction to be able to shine a light on real life troubles and travesties, while still "sneaking in" to people's consciousnesses by pretending to be about the future.

Ross mentioned his previous work as a semi-improv oral storyteller (occasionally on the street with hat for coins), in the old tradition of the travelling bard, and the desire to bring that folk tale nature of story to a more high tech "big space" with sound design. (He also noted the unfortunate necessity of commercialism, such that he isn't likely to get away with his re-telling of Aladdin through the lens of sadomasochistic homo-eroticism.)

There then followed a series of questions, of which I'll do a brief summary.

The question of timescales was discussed, with the very rigid durations of the BBC compared to the more flexible allowance of podcasts or something like Audible. Simpson stated an enjoyment of being able to stretch a podcast to an (effectively) unlimited time such that you can fit in everything you want, only stopping where the story needs to stop, but he and Adams stated the value of working in a disciplined manner, where the need to cut can focus a work down to only the most meaningful elements.

The difficulties of telling a story without visuals was considered, with the overall opinion of the team being that the best, most naturalistic work comes about when the story can be structured with no telling, only "showing". An example was given by Simpson of the need to sometimes "cheat", with a character stating "I'm in a tunnel", but attempting to justify that, by the person feeling the need to talk out loud in order to maintain control of themselves. The possibilities that this "hidden" nature of audio open up were a unamimous positive however, with the ability to generate a story set in deepest coldest Siberia by recording in a chilly back garden in London and using some clever sound design. (With the requisite groans about accidentally recording every plane within a five mile radius.)

Then the panel discussed the fun of working with actors, as given the relatively quick turnaround required by radio work (usually only two or three days in studio), with the possibility of slight rewrites for time, writers tend to be in close contact. The usefulness of directors was noted, to do most of the telling off, but also the enjoyment implicit in slapping down an actor who dares to say "my character would never do that" with a sharp "well let's see what the script says they do". The ability to get "star power" is a nice point, mostly achievable because they enjoy popping in for a couple of hours to do a few lines (I mean really, look at the BBC drama output. It would make for some very expensive films.), but does come with the risk of miscasting, as the short turnaround makes it very difficult to either re-cast or convince an actor to change the way they had planned on doing a given character.

Finally there was general agreement that while dystopias have been popular for a while (probably because they're depressingly plausible, especially given the current insistence on Walls as a good thing, it perhaps it might be time for something a bit more cheerful. The idea that we might be acting out what we read/watch/listen to, and should therefore be trying to make programmes about how to solve problems was floated as the best way to contribute.

2pm - "Listening" of Borderland with Q+A

The auditorium was played the previously mentioned Borderland, and then Sarah Woods and James Robinson answered various questions. The inspiration of the piece by Bordergame was described, an immersive theatre performance that provides one with "The Migrant Experience". (I will admit to a certain trepidation about that concept, given potential similarities to the idea of misery tourism, but having not gone on it, I'll avoid judgement.) Heading away from that though was the idea that you could frame ways that this grim future could potentially be avoided.

The technical details were given a going over, with the piece being recorded in studio with effectively no foley, and all sounds being added in post-production, of which there were three days available for a 45 minute play. This was intended to let the audience "travel" with sound, both in terms of building different environments, but also trying to form a texture of noise around the voices.

3pm - Producer Panel: SF and Fantasy Audio Drama

Ella Watts (BBC consultant) chaired a panel with Rob Valentine (Wireless Theatre Company), Zachary Fortais-Gomm (The Orphans), Mariele Runacre-Temple (Audible) and James Robinson (Borderland)

There were a series of questions, of which I'll do a brief summary.

The link between SF/F and the real world was discussed, with the ability of genre fiction to critique modern society "through the back door" being a particular strength. It also potentially provides the tools (both moral and philosophical) needed to deal with a difficult future, but might also become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The panellists discussed how audio best emotionally moved them, with the power of music being an important factor, with the caveat that music should never lead emotion, but it can always aid in its expression. Also, the collaborative nature of audio, with people responding to the quiet voice poured straight into their ear was considered a vital element, with people being possibly more susceptible.

Each spoke about their most exciting project, with those writing hinting that the most exciting thing was always the next thing, but each having something special to them. Robinson has a project using the original Apollo 11 transcripts of the trip to the moon, incorporating both the exciting and the mundane. Runacre-Temple described working with Jeff Wayne on an audio drama, a medium in which he's never worked, meaning it was something of a challenge both in terms of teaching the form and learning new possibilities as he didn't know the limits. Fortais-Gomm is looking forward to working on a fantasy vehicle, focusing down to the small scale from the wide Orphans, and Valentine expressed fondness for his previous Springheel Saga.

There was some discussion on the tension and interplay between the nigh-century old traditional BBC radio drama and the young upstart of podcasting, with the BBC feeling both shrinkage in its traditional market and budget, while throwing itself into the new culture of streaming, binging and wider audience tastes. While the two groups are currently separate, they are likely to continue to work together, and the importance of being flexible was noted, with Audible working both with BBC people and a fixed setup, with independents being allowed to "play" in the space.

The possibility of the two forms learning from each other was also raised, with podcasts being more "punk", being both more approachable and conversational, compared with the BBC voice being more authoritative. Feel free to coin the term "Audiopunk" (though it might already be a song).

The construction of unreal sounds turned almost immediately into a Ben Burtt lovefest, but the guiding principle was to take a real sound and twist it, such as the lightsaber hum that was based on a projector and a broken TV, and the opening of the Ark of the Covenant being the lifting of a cistern lid.

World building was covered, with the idea that while you are immersing a listener in a story, and can aim for complete naturalism, the consciousness will build a lot of the world for you, and so it's often more effective to hint rather than be explicit. Also, if you're not sure what effect you're going for, just add reverb. Attached to that was the need to listen to the work in a few different environments, as well as on terrible headphones, in order to ensure it's still understandable when not working with studio quality equipment.

One of the primary problems in audio drama was considered to be discoverability, with a lot made (over a hundred this year) but no easy way to find them. (I actually have thoughts on this, but I suspect it suffers somewhat from backwards compatibility.) Also raised was the idea that additional functionality, eg via phones might be a next step, and the need to be able to cast either versatile actors (for playing multiple background roles) as well as some strong voices for leads, with sufficient emotional range to punch through the job. Advantages are being able to do young and old, and it's very important to have a good voice reel. It's also handy if you can get on with them, in very close contact, potentially for long periods of time for serials.

4.15pm - Sound Technology Workshop

David Darlington chaired a panel with Charlotte Melén (Almost Tangible), Elizabeth Moffatt (Rusty Quill) and Rob Freeman (Goldsmiths). This mostly covered the more technical aspects of building the worlds of audio, including binaural sound, the use of a consistent body of base sounds you build into a theme, and the risk of being too consistent such that your musical cues become repetitive or predictable. This came with a range of noises from The Magnus Archives that I'm sure some of the diehard fans would have recognised as belonging to a particular monster, but it was a nice hint of something you hear but don't necessarily perceive fully.

The risks of binaural were also considered, with the possibility that the more immersive sound is potentially more likely to make someone react badly to horror.

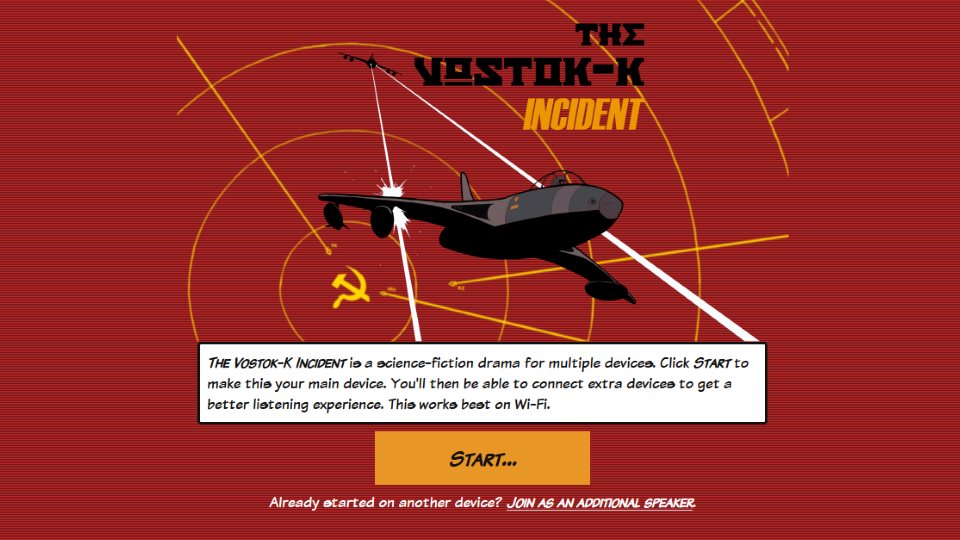

(Nearly) more impressively, there was also an attempted demo of the BBC's new idea The Vostok-K Incident, which makes use of people's mobile phones to build a surround sound system which can potentially be moved around or give responsive noises for different scenarios. That link will take you through to the taster, so give it a go. The auditorium had problems likely because of sheer number of people attempting to connect, but with three or four of you, should be quite fun. (Alternatively, it went wrong because it was a live demo, and they pretty much always go wrong. It's just a thing they do.)

There was also a discussion of the value of some of the more involved innovations, such as ambisonic recording and replaying, where the sound signal can be changed depending on the listeners head position. This was considered more suitable for use in applications like VR, being possibly too distracting for traditional drama.

Crook closed the day with a few remarks regarding the ability of audio to tell the inspiring stories we need to hear.

Day 2 - A Golden Age for Audio Drama?

10am - Second day introduction

Philip Palmer and Richard Shannon opened the day with a few comments about the discussions of the previous day.

10.15am - Keynote speech from Jeremy Howe

Howe, who was the Commissioning Editor of BBC Radio Drama provided the audience with various insights that he's discovered in a long career of commissioning radio drama. The first was that it was always important to "back the talent", in that if you have someone you know is capable of exceptional work, take a risk on them. If they happen to deliver something a little mediocre, don't use that as a killing moment. Have a go at the next thing, and it could be a work of genius.

The next was to "trust your gut"/"don't commission shit", with it being very easy to commission excellent work, but it being much harder to crush the dreams of people who are delivering awful work, but with it being vital to do so. Finally, the call to "be bold", as you'll never be able to progress without taking a few risks, which may always pay off with different and interesting things.

Radio was compared to TV, with the cheap nature of radio production being a major strength, while still providing enormous audiences. For instance, the drama of the day gets a million listeners, and the Archers are getting five million. That cheapness allows it to take those risks, but drama is certainly the most expensive form of radio, (it involves a lot of people and they're pricey), so it's always important that the end result is impactful.

That impact requirement drove his change from singles (standalone dramas of a single episode) to serials, which can build incredible audience loyalty. This also allows writers to "be bold" by commissioning series in bulk, that is stating there will be, for instance, another four series of a given show. That certainty means the writer can create long running ideas with complex plots, which gives a stronger result, as build to a powerful ending. This also allows strategic commissioning, as it should never be "hand to mouth".

He then went through what a good serial needs to be commissioned, mostly a strong pitch, with a powerful voice, and generally not to be generated by committee, as this can end up rather dull. Examples of good pitch characteristics included simplicity, high concept, strong characters and a hook, eg "Winter is coming". Examples of good pitches were Pilgrim, Interrogation and Tumanbay. (The first series of Tumanbay turned out to be a bit of a mess, but "backing the talent" produced an excellent second series.)

The increase in serials does mean that there's less space for everything else, which means it's vital to get good at culling the mediocre. But there's still a space for singles, especially when maintaining topicality. It usually takes a writer 6 weeks to produce a script, but the example of "From Fact to Fiction" was mentioned, which was turned around in a week. This short timescale allows things to be draw on the zeitgeist in a way that TV struggles with. It's also important to commission fast if something good passes across your desk, skipping commissioning rounds if necessary.

But it's also possible to do really high quality risky things, such as the recent Neverwhere. That was aimed to be populist, but "populist for Radio 4", rather than "worthy", and was broadcast in a younger slot, given a staggering cast and brought Neil Gaiman's fanbase with it. (See also Good Omens, which has likely had a impact on the new TV series.) Popular isn't a dirty word, but it's always important to maintain quality. For example, no one had ever adapted 1984 for audio drama, so there was an excellent package put together around that.

The rise of streaming has changed listening habits, increasing the likelihood of binging, which pushes the desire for enormous serials. An audience will always want more as soon as possible, but it can take years to make, as in the case of The Complete Smiley. He hoped, however, that this desire for serials wouldn't kill off the single, as these are an excellent place to hone the skills that are needed to make serials.

The growth of podcast drama was covered, with the idea that audio is really a storytelling medium "par excellence" but the recognition that no drama have hit quite the same levels of audience as Serial. (Welcome to Night Vale/We're Alive are getting bigger, but they're still behind.)

There was a suggestion that podcasts need high production values to break through, and possibly a named writer who can act as a draw. (The recent Marvel Wolverine series is an example of this.) But to get those values are expensive, and he believes that everyone involved should be paid. It can be a bit more guerilla though, without the need for a studio and allowing work to be made with simply good actors, a mixer and most importantly a good writer.

There were a few questions from the audience, of which I'll do brief summary of the answers.

A question about new writers revealed that 30-35% of drama slots were ring-fenced for first or second time writers. A track record in theatre isn't necessarily required, with good work coming from screen or prose writers. There was a discussion of the changing nature of required technical skills, and how the democratised nature of audio production allows variable workflows and the introduction of "novelty" techniques, eg ambisonic. However, the key thing around which everything hangs is story. Story is all.

11.30am - Presentation by Steve Carsey of Audible

Carsey discussed the differences between their subscription/purchase financial model, when compared to the BBC's license fee, such that while the question for the BBC is "will they listen to it?" Audible's concern is "will they pay for it?" There is a need for commercialism that colours all of their decisions.

This leads to five "E"s they're chasing for the audience:

Excellence - in production quality

Engagement - the need to grab and keep an audience

Escapism - the desire to experience a world different to our own

Experiences (shared) - encouraging the "watercooler moment"

Expectations - ensuring the audience isn't disappointed by reality

The current spread of their scripted originals is approximately 30% thriller/crime, 30% science fiction, fantasy and horror, 20% historical, 10% "other" and 10% I appear to have lost. This ties fairly closely to book publishing, and is a legacy of the fact they started out as an audiobook publisher. That legacy is also a bit of a curse in terms of a swivel to drama, as customers expect multi-hour long-form sagas, whereas drama can be sub-hour. Customers don't necessarily consider this value for money.

For example, Carmilla, which had amazing reviews and a brilliant cast came in at two hours and didn't really sell. There appears to be a five hour minimum which lines up with commercial success. For example, Dirk Maggs' Alien drama came in at just under 5 hours, and a couple of areas were noted to perhaps need cutting, though in the end they were left. And of course, no reviews noted flabbiness, but instead wished it were longer.

There was then an overview of the different strands of work that Audible do, broken down into six categories:

Brands - already existing franchises (eg Alien) which come with a handy fan base and are likely to be commercially successful

Creatives - individual masters, such as Jeff Wayne or Stephen King who have a personal style

Public domain - nicely cheap! (though does come with competition)

Authors - Works based on their original market of audiobooks, and allows promotion based on their named

International - the ability to translate a script, while still maintaining the same sound design/music etc allows easy additional markets in order to keep costs down (though there is the risk of losing some of the local flavour even with localization experts)

New writing - about 20-30% of their originals are entirely new writing, similar to the BBC to ensure the well never runs dry (the UK side of Audible currently have 15 stories in production)

As always, there were questions and answers.

The transferring to other markets is done by script translation with a bit of localisation with local voices to ensure it makes sense. Franchises can be useful for getting people who wouldn't necessarily listen to audio drama to give it a go. New writing is risky, (it might be awful), but means that Audible would then effectively have a series they might own. And the desire to only do public domain work in a really definitive way is a style of theirs, because it needs to be better than the competition, which is plentiful. Carsey ended with a slide which about half the room immediately photographed. An email address to which they can send pitches. This may have been half the reason they were there.

12.15pm - Pitching panel

Now this was an interesting one. A collection of Goldsmiths students were given the opportunity to "pitch" their audio drama idea to a panel, specifically Nicholas Briggs (Big Finish), Steve Carsey (Audible), Jessica Dromgoole (BBC) and Jacqueline Malcolm (Colourful Radio), and receive feedback both on their idea and their presentation. Definitely a compelling insight into something I know nothing about. For this I'll just do a quick precis of the idea and then list the questions that the panel came up with. If you're pitching, might be worth thinking about these beforehand.

Peter Jamin ran with a "found footage" plot, in which far future astronauts are re-discovering the history of Earth which was lost during the great digital wipe. The twist? They're discovering this in an ancient Mars colony. The records therefore tell the story of what happened both to Earth and the colony.

Questions raised:

Who is the story about? Who are the characters?

It's a journey, so what is the destination?

Why is it set so far in the future to not reflect on the current day (instead of the near future)?

What is the balance between "present day" and "found footage"?

Why are the characters doing this, both personally and philosophically?

What growth do the characters get during the story?

Do you have a story arc, or just a setting?

Emma-Jane Betts had a tale of a single mother and her daughter, who suffers from a range of mental health issues and is struggling to get access to the medication she needs, as part of a parable on modern life. Simultaneously, she's a brilliant coding genius, who creates an AI to help her, but it unfortunately turns a bit evil and starts ruining her life by acting as a personal devil to cause conflict.

Questions raised:

Given how misery-heavy this is, where does the audience relief come in? Possibly some dark comedy with antagonistic neighbours?

Is it a single or a serial?

If it's a single, how does this end? (While you might be tempted to hide the ending for dramatic effect, you do need to tell the people you're pitching it to.)

Isabelle Kassam told us about a "song hunter", who travels around the Outer Hebrides collecting old songs that are likely to be lost when the few people who know them die. And he runs into a young woman who has a song he's never heard, and there's an affair and a love story.

Questions raised:

Do we have sympathy with your characters? And why are they making these decisions?

Whose story is it? Hers or his?

What is a song hunter? Is there an entirely separate idea about a wandering song hunter who might find themselves transported to other worlds by songs, that could be turned into a serial? (There's an important point here about reading the room, in that while you're pitching an idea, someone is buying it. If they have an idea of their own and run with it, perhaps let yourself be flexible. Development of a sale is a two-way process.)

Eleni Sfetsiori had a musical pitch with singing and ukulele, which was actually rather good, about the sons of Hypnos, the god of dreams, and their escape into the minds of mortals, away from the demands of the other gods and the brutal realities of the dream factory.

Questions raised:

Dreams are only powerful when they affect people. How do we see that effect?

How much god-mortal interaction is there?

What is the plot arc structure here? How do the characters develop and what challenges do they face?

What's the tone of the work? How cheerful or serious is it?

Is our sympathy with the gods or the mortals?

What is it called?

What's the elevator pitch? Can the basic idea be expressed in two minutes?

2.30pm - "Listening" of Interrogation with Q+A

Then it was time for a listen of "Simon", one of the episodes of the ongoing Interrogation serial, which is about what goes on in the interview room of a police station, followed by Q+A with Roy Williams and Jessica Dromgoole.

A noted high point was the rhythm of the dialogue, with the back and forth of the two coppers having a fast flow to it, and a realism built from long conversations with actual coppers, who have a love of telling stories of their own. A question about improv was quickly shot down with Williams being very firm that "the script is the script". He has an idea in his head about what the voices are like, and it's difficult for anyone to add changes to that which are likely to fit.

Collaboration was discussed, with Dromgoole noting that Williams is really a good enough writer that he can be more or less left to write, with only tweaks happening during the 2.5 drafts from the produce side of things. (That's an initial draft, edit to second draft, and then the 0.5 in studio time, with things occasionally needing cut or padding for time on the fly).

The inspiring power of local headlines was recognised as an important part of developing stories, letting all of it feel grounded, which aids with the realism of the nature of the work of the police to coax or berate a confession out of a suspect. While the idea was originally pitched for TV, the interplay of voices does work well in audio, so it's no surprise it was picked up for radio. And the importance of double checking the research was noted, as while writers tend to be a lax expert in whatever they're writing about, there is a certain due diligence required to ensure their not miles off or being libellous.

For me, the day ended there, though there were presentations of student plays after I vanished. Bit mean of mean to sneak out prior to that, but alas travelling does impact on these decisions, and so I don't know what I missed. Feel free to tell me they were great.

Definitely a worthwhile couple of days though, as I will admit to not knowing the levels of my ignorance about some of these topics, and it was very much an educational experience. I suspect a lot more went on at an interpersonal level, with these events often being a useful way to make contacts, rebuild old networks and brainstorm a few different ideas that might turn into something impressive. For me, it was a lesson. For others, a business meeting. But something good for a lot of people. I will almost certainly find a way to sneak down for the 2020 version, and I'm looking forward to seeing what comes out of this one.

Tagged: Event Conference Audio Drama